Through the Eyes of the former Consul General Yamada (June, 2017 - July, 2020)

2017/11/2

75th Anniversary of the Internment of Japanese and Japanese Americans

Approximately three months after the attack on Pearl Harbor by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942. With this order, about 120,000 Japanese and Japanese Americans living on the West Coast of the U.S. were forcibly removed from their homes and incarcerated at “War Relocation Centers,” located at 10 different sites throughout the United States.Even before World War II, Japanese and Japanese Americans experienced many forms of discrimination. In Seattle, they were restricted to reside only in certain areas, and could not use the same public venues, such as the pool or movie theater, as white people. When the war began, they were lumped together as “enemy foreigners” and removed from their homes and livelihoods just on account of their Japanese ancestry. They were only allowed to bring a minimal set of belongings to the internment camps, and thus all their fortune and land that took many years of hard work to achieve were relinquished at throwaway prices. At the Panama Hotel – the then center of Nihonmachi (Japan Town) in Seattle – you can find today a glass panel on the floor, revealing its basement and the piled-up suitcases that they had to leave behind at that time.

Camp Harmony (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

The around 7,700 Japanese and Japanese Americans living in Seattle and its surrounding areas were gathered at the Puyallup Assembly Center, and later sent to internment camps such as Minidoka in Idaho, where they spent three years until the end of the war. The internment camps had barbed-wire fencing that stretched around the sites, and machine guns were installed on the monitoring towers that pointed toward the inside. The internment camps were located in secluded areas with harsh living conditions like the desert where the winters were bitterly cold and the summers scorching hot. Several family households were made to live together in the same wooden-barrack tenement houses. All the shabby toilets and water supply were shared, and there was no such thing as privacy.

For the Nikkei (American citizens of Japanese descent), who had loyalty and patriotism to the United States, the forced seclusion due to their family ancestry was an unfair and humiliating experience that went against the nation’s fundamental principles. To demonstrate their loyalty to their country and show that they are true Americans, the 442nd Infantry Regiment, composed of Nikkei who volunteered in the U.S. Army, fought heroically and made spectacular achievements while having sacrificed many lives.

After the war, a majority of Japanese Americans returning from the camps to general society did not want to talk about the disgraceful experience of incarceration, and therefore the movement to fully recognize the lives of those who suffered in the internment camps did not come to the forefront until the 1970s. During President Carter’s term, a full-scale investigation about the incarceration of Japanese Americans was opened and the finished Commission’s report was submitted to President Reagan. According to the report, it was found that Executive Order 9066 could not be justified by a military need, but rather was a product of racism, wartime hysteria, and a failure of political leadership. Therefore, President Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, which officially apologized for the incarceration of Japanese Americans on behalf of the U.S. government and authorized the payment of $20,000 to each camp survivor.

The circumstances surrounding this dark chapter in history were well-summarized in the August 2017 issue of the magazine “Lighthouse.” A noteworthy organization that keeps the history alive is DENSHO, founded by Mr. Scott Oki, Mr. Tom Ikeda and others. DENSHO keeps records of interviews with Japanese Americans who experienced life in the internment camps. DENSHO preserves these saved accounts, and continually updates its website (https://densho.org/), making the large amount of oral stories available to the public.

75th Anniversary – Remembrance of Puyallup Assembly Center

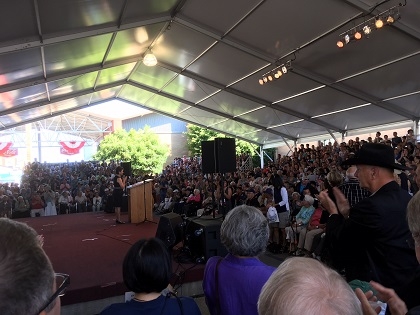

A remembrance ceremony for the 75th anniversary of the Puyallup Assembly Center’s establishment (known as “Camp Harmony” at the time) took place on September 2nd this year. More than a thousand people gathered for this important occasion. To this audience, Mr. Tom Ikeda related the episodes of what happened at that time. Master of Ceremonies Lori Matsukawa called the name of each survivor of the internment camps; they responded by waving their bamboo sticks. The occasion also recognized those Americans who did not concede to participate in the discrimination that was based on emotional “Japanese hatred” at the time of Japanese-American incarceration; despite receiving criticism from the rest of society, they preserved the fortunes of their Japanese-American friends until their return after the war. These brave and rare acts make us recall Mr. Chiune Sugihara, a Japanese diplomat during WWII, who ignored orders from the Japanese government and helped Jews flee Europe by issuing transit visas, saving many lives. Pierce County Executive Bruce Dammeier’s grandparents are examples of these Americans. At the ceremony, the immense gratitude felt by the Japanese Americans was expressed to the descendants. I felt the determination of the Japanese Americans in that the important lessons of history should be passed on through the noble acts of these Americans.

Through this ceremony, I felt that I was able to better understand why Japanese Americans are so well-respected in Seattle. They have vowed not to forget what was inflicted upon them, but on the other hand, refuse to be dragged by the past and cloud their eyes in the present. Instead, they are trying to utilize these lessons from history to educate the future. It is impressive what positive attitudes the Japanese Americans have shown, not just in their hard work and sincerity since their initial immigration to Seattle, but particularly in their efforts to overcome the past that had been unfairly handed to them. I believe that it is in great part thanks to the noble spirit of Japanese Americans who had gained respect from the United States that Japan was acknowledged and accepted by the United States with such close affinity despite a bitter war. In other words, their deeds and attitudes are the foundation upon which today’s Japan-US relationship was born, based on trust and friendship. While reflecting on these thoughts during the ceremony, I felt deeply proud that I share the same blood as these Japanese Americans.