Soft and Fair Go Far

In the summer of 2020, the Olympic and Paralympic Games will be held in Tokyo. Within Japan, there is much anticipation regarding our own “homegrown” martial art of judo. In my view, judo’s appeal comes from three important traits: it is first and foremost a form of self-defense, it emphasizes respect for one’s opponent, and small-bodied individuals can win by using the power of their larger opponents to their advantage.

There is a saying in Japanese that gets to the essence of judo: 柔よく剛を制す (Jyuu yoku gou wo seisu). It can be translated as “Soft and fair go far,” or, in other words, “flexibility often gets the better of brute force.” There are many old stories of encounters between legendary judoka (judo practitioners) that illustrate this. One story involves Yoshitsugu Yamashita, one of the “Four Guardians” of the Kodokan, and a disciple of Jigorou Kanou, the “father of judo.” Yamashita was also the first judo practitioner to ever achieve the rank of 10

th dan. In 1903, when Yamashita was 6

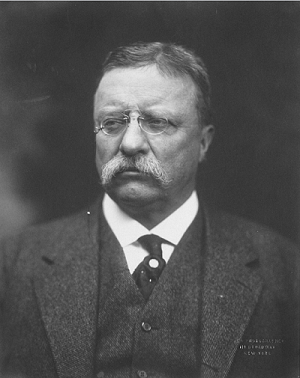

th dan, Kanou sent him to America. After performing a demonstration in Seattle, he continued east to Washington D.C. The U.S. president at the time, widely regarded as the most dynamic U.S. president in history, was Theodore Roosevelt. With Roosevelt in the audience, Yamashita sparred with an enormous wrestler. Yamashita was about 5 ft. 4 in. (162 cm) tall and 150 lbs. (68 kg), while his opponent was 6 ft. 7 in. (200 cm) tall and 352 lbs. (160 kg). Yamashita was able to pin his opponent to the ground and win the match. Greatly impressed, President Roosevelt asked Yamashita to teach him judo. The president practiced three times a week and eventually became the first American to earn the brown belt (1

st – 3

rd kyu [grade]). Yamashita went on to teach judo at the U.S. Naval Academy and Harvard University, while his wife, Fudeko, taught the art to ladies of American high society at the time.

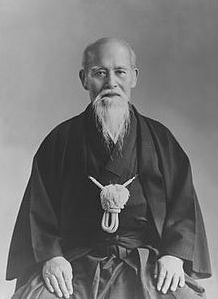

I am also fond of a similar episode involving Morihei Ueshiba, the founder of aikido. Ueshiba was initially a judoka, but while trying to find a way of using one’s body in the most logical way possible, he devised a method that allows smaller individuals to easily pin down larger opponents, which developed into the art of aikido. Once, when Ueshiba was on a train, he encountered a famous judoka sitting in front of him. This was in the 1930s, a time when it was not uncommon to encounter tough machos swaggering around town with an air of propriety, eager to show off their prowess in combat. Ueshiba held up his little finger to the judoka. “Try and break it,” he said. The judoka at first refused to spar with Ueshiba, who, at the time, was over 50 years old and 5 ft. 1 in. (156 cm) tall. But when Ueshiba repeatedly insisted, the judoka became annoyed, and in order to shut him up, grabbed Ueshiba’s little finger, only to be thrown to the ground in an instant. The judoka became a disciple of Ueshiba and learned aikido from him for over 10 years. After seeing Ueshiba perform aikido, Jigorou Kanou is said to have remarked, “This is the judo that I am after.” これこそが私の理想とする柔道だ.

Nowadays, judo, like boxing and other sports, is divided into specific weight classes, so we aren’t likely to witness the exciting spectacle of a small-bodied judoka throwing a much larger opponent. Still, I believe that the main reason for judo’s worldwide popularity is the fact that it teaches techniques that allow practitioners to defeat larger opponents. I suspect that its emphasis on cultivating one’s mental faculties and effectiveness as a form of self-defense are other factors which have made this martial art popular among women.

On December 13, at a conferment ceremony held at the Official Residence, two judo dojos run by Japanese Americans in Seattle received the Foreign Minister’s Award. The Seattle Dojo was established by Iitaro Kono (2nd dan) in 1903, and after 116 years it is the oldest dojo in North America. When war broke out between the U.S. and Japan, and Japanese Americans on the West Coast were sent to incarceration camps, the dojo was unable to continue its activities. After the war, it reopened in 1947 and established itself as a hub for judo in the Seattle area. Another dojo, the Budokan Dojo, was established in 1968, and saw its 50

th anniversary in 2018.

At Official Residence: (Left to right) Misato Nakamura, Alan Yamada (Seattle Dojo), Patsy Yamada (Seattle Dojo), Mitsuko Terada (Budokan Dojo), Alvin Tereda (Budokan Dojo), Yoichiro Yamada (Consul General of Japan). |

Over 100 people were present at the event, including leaders from the American Judo Association, as well as many children learning judo. Japanese judoka Misato Nakamura was also in attendance. Ms. Nakamura obtained three gold medals at the World Judo Championships. She also won two bronze medals at the Beijing and Rio Olympics in the 52 kg weight class. Last fall, she spent three months in Seattle teaching judo at both dojos. Ms. Nakamura said her dream is to someday open her own dojo and teach judo there.

I would like to sincerely thank Japanese Americans for the vital role they have played in furthering U.S.-Japan relations. The origin of the current interest and understanding of Japan that exists today in American society can be traced back to Japanese Americans practicing traditional Japanese culture, including judo since pre-war years. With the Tokyo Olympic and Paralympic games coming up in 2020, I would like to wish the judoka from both dojos the best of luck.